For the Around the World series, I am still finishing the reading from South African writers.

Apartheid: A Collection of Writings on South African Racism by South Africans, edited by Alex La Guma, is of course the book with which I started the reading.

Its essays, by expatriates who are far-flung in Europe due to their opposition to the apartheid government, lay out the racial political, economic and cultural structure of apartheid by the time the book was published. (Ironically perhaps, given colonial history, the book was published in London, 1972.) Land allocations, education, defence spending, the entire history of the colonization of South Africa are knowledgeably sketched... I think the interspersed poems, pan-African themes and all, are meant as seeds for a free post-apartheid culture.

|

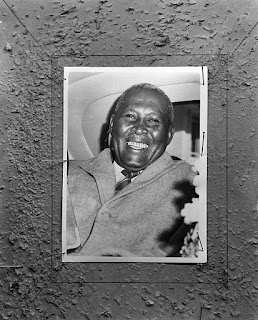

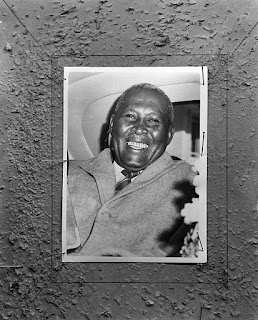

Albert Loethoeli, leider Zoeloes in Zuid-Afrika (1967)

(Albert Luthuli, leader of the Zulus in South Africa)

From the Nationaal Archief, Netherlands

via Wikimedia Commons |

Long Walk to Freedom (Vol. 1) by Nelson Mandela and Let My People Go by Albert Luthuli offer two perspectives on the fight against apartheid. Mandela (a member of the Xhosa people) came from a more prestigious background, and also appeared to benefit by the pre-apartheid reality more, and has more rigour and skepticism and lordliness. Luthuli (a member of the Zulu people) came from a less prestigious background, working as a teacher in what he describes as a cloistered academic environment for well over a decade before becoming a less well-paid chief; he also embraced Christian precepts to an extent that makes him feel more idealistic and gentle-tempered —most of the time. Like my paternal grandfather, one can sense bedrock underneath his mild willingness to find out what other people want and to let them have their way. Both Luthuli and Mandela, of course, became Nobel Peace Prize laureates.

A South African colleague, when I asked him, conceded that I could theoretically look into many classics of South African literature (Nadine Gordimer's work and Alan Paton's amongst them). But he suggested skipping them — instead, exploring contemporary South Africa and urban crime through the lens of Zoo City by Lauren Beukes. I'm still hoping to come across an ebook version; but, failing that, the audiobook is an option.

*

As an accidentally companionable read, I am also reading more of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o's non-fiction and criticism. Although his personal experience of colonialism and neocolonialism centres on Kenya, he alludes in the particular works I'm reading to the South African apartheid state — not yet dismantled at the time he was writing. Apartheid would only crumble in 1994. There's also a tragic element in the knowledge as a reader from the future, of the impending bloodshed in Rwanda.

I've become impatient with the rote Communist passages — I can only read 'join hands with the proletariat' or 'comprador classes' so many times, without feeling that these phrases lose all meaning — in these essays/speeches. And I suspect that he turned into a self-conscious Hero of the Lecture Hall type of academic in his later years (I say as a disgruntled former undergraduate). But Moving the Centre: The Struggle for Cultural Freedoms is fascinating as a geopolitical time capsule of the 80s and 90s.

I do feel awkward when Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o writes of the need to write in African languages, not English or French or Portuguese, and he celebrates writing works in Gikuyu. In the end I am reading his celebration of writing in Gikuyu in English, because that is accessible to me.

His writing in Moving the Centre is less raw than the writing in his prison memoir Devil on a Cross, but the mood remains invigorating. He is always resisting.

To know a language in the context of its culture is a tribute to the people to whom it belongs, and that is good. What has, for us from the former colonies, twisted the natural relation to languages, both our own and those of other peoples, is that the languages of Europe [...] were taught as if they were our own languages, as if Africa had no tongues except those brought there by imperialism [...]

and

'A peaceful country, don't you think', he [a colonial farmer] would say turning to the house servants who stood by ready to serve him his breakfast. And the house servants would also stand on some of the bodies but at a respectful distance from the master and they would chorus back: 'Yes master, peace'.

***

Stamped from the Beginning by Ibram X. Kendi is proving challenging and rewarding, an indispensable and amazingly researched completion of any picture of European and American politics from the Renaissance onwards, and a gem to any history enthusiast who is genuinely curious. A few passages are horrible to read, like the fate of Sarah Baartman, the 'Hottentot Venus,' who was treated essentially as a laboratory rat by scientists of the late Enlightenment and early Napoleonic era.

*

In British contemporary literature, I started listening to Summer by Ali Smith.

It is a stream-of-consciousness third-person-narrative novel from 2020, of the musings of an English teenager on political news as she grapples with homework, her parents' separation and her brother's predicament.

The book is well-written and critically acclaimed.

It is also very 'of the moment' as it talks about everything from the deported British residents of the Windrush Generation through Trumpism to Australian wildfires. But I don't like remembering the times where I 'burned at the stake' of world politics as much as the teenager in this book. To be fair, likely the author's own angst derives from Brexit, which is generally not felt as the deep crisis of economics, politics and social culture, the daily emotional torment, in Germany that it is felt to be in the UK itself. But at least I walked in protests against the War on Iraq instead of just complaining at home.

That feeling of not wanting to read hundreds of pages of aimless whining, however literary and however near my own political orientation, was why I did not finish the book.

|

| Cover of Summer, via Penguin Books UK |

(The narrator of Summer's audiobook struggles with the repetitive 'he said' and 'she said' that dot the dialogue. This dialogue, in its faster rhythm, does bring movement and pace to the book. Therefore I found myself wishing that Ali Smith had written a play instead.)

*

In preparation for Canada Reads 2021, the televised competition will broadcast starting March 8th on CBC, I have begun reading Butter Honey Pig Bread by Francesca Ekwuyasi. Magical realism a little along the lines of Toni Morrison, it begins by telling the tale of the childhood of a spirit that tends to slip away from the living world.

(Content warning: There's menstrual blood in an early chapter, so the easily shocked should likely find a more soothing book to read; and also serious subject matter like stillbirths etc.)

|

| Cover of Butter Honey Pig Bread, via Arsenal Pulp Press |

It's not self-consciously literary — you never feel like the word choice is stiltedly signposting its own excellence, even while it is excellent — nor pretentiously enigmatic.

*

Buck Naked Kitchen has a risqué title, but it's a respectable Canadian cookbook, published last year by Kirsten Buck. It has become a favourite of mine to the degree that I am sprinkling around good reviews around the internet.

I don't follow the Whole 30 Diet, which is a main nutritional inspiration for the book. But it's easy to stick to the more permissive recipe variants.

My family favourably reviewed the Smashed Potatoes with Roasted Red Pepper Sauce when I baked them the day before yesterday, as well as the pepper maple syrup bacon, so these appeal even to traditional tastes. I also liked the more consciously healthy or 'new-fangled' recipes. The Creamy Cashew Milk was frothy and sweet. The Perfectly Cooked Wild Rice was well cooked as promised: nutty and lightly salty and nicely grainy without being hard. And I've been making Buck's variation of a Fruit and Nut Trail Mix — walnuts, cashews, coconut flakes, hazelnuts, sunflower seeds, pumpkin seeds, dried goji berries and blueberries and white mulberries — for my brothers. It's filling and has a nice balance of natural sugars and colours.

The cookbook's healthy ingredients (well, all right, I guess the bacon is debatable as a healthy ingredient), when mingled imaginatively, can have an experimental flair while being as satisfying as steak and potatoes.

|

The author of Buck Naked Kitchen,

via Penguin Books Canada |

It was also pleasant to see the peaceful photography: daytime lighting and a leitmotif of green plant life.

The idea for soup-to-go came to me while on a fall hike in the Whiteshell Provincial Park, located in southeast region of Manitoba along the Ontario border. The wind coming off the water was cold enough to give me a chill. Instead of the energy bar I packed, I really just wanted something to warm me up.

Earlier in the week I had made the saffron rice from Yotam Ottolenghi's and Sami Tamimi's 2012 Jerusalem cookbook. It turns out that I dislike the flavour of saffron, even if the barberries were tasty. But I also undercooked the rice — not the recipe's fault, I am certain, because I used brown basmati rice instead of white basmati rice. The dill and white pepper instead of black pepper are important to the flavour, blending into and softening the stern flavour of the saffron, and I was impressed that the authors had figured this out.

|

| Cover of 100 Cookies, via Chronicle Books |

Lastly, I've begun baking recipes from Sarah Kieffer's 100 Cookies, an American bestseller in 2020, beginning with the soft chocolate chip cookies recipe. It is as regimented as Buck Naked Kitchen is flexible. Before the recipes begin, there are firm instructions, rather than idyllic word-paintings of kitchen escapism.

While Ottolenghi can be precise enough and I've grumbled in my head about the fiddly gram measurements and the need to measure fractions of a centimetre, it was only with 100 Cookies that I felt like I was baking with a fastidious superego looking over my shoulder.

But my family, of course, just experienced the final result. They made blissful, Cookie Monster-like gestures as they ate the doughy, freshly baked cookies with the chocolate melted and gooey in them.

So, in the end, weighing out each 45-gram sphere was worth it.

*

Aside from Buck Naked Kitchen, Barack Obama's A Promised Land has become a 'comfort read.' Since I followed the news so much during the 2008 financial crisis, etc., the book is illuminating the past, as well as setting a 'prologue' for the not-identical-but-similar challenges of the Biden Administration. Besides, it calms my anxiety when turmoil arises in the workplace.

.jpg)

.jpg)