One thing that's delightful to read across religions, philosophies, and tales is the explanations we have written down for the natural world that surrounds us.

Sitting at my laptop on a grey January day in the Northern Hemisphere, the coal stove fired up, buds still rarer on the oak twigs outside the window, green bulbs beginning to form on the forsythia indoors and a hyacinth bursting into pale pink blossoms on the windowsill, of course looking at winter makes sense. And I'll also reach back further in time than I've done lately on this blog.

***

|

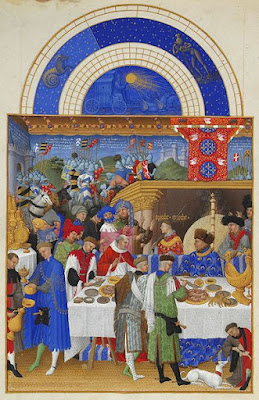

| Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry Folio 1, verso: January ("A New Year's Day feast including Jean de Berry") by the Limbourg brothers (fl. 1402–1416) via Wikimedia Commons |

Pliny the Elder wrote in his Natural History:

THE world and thiswhatever other name men have chosen to designate the sky whose vaulted roof encircles the universe, is fitly believed to be a deity, eternal, immeasurable, a being that never began to exist and never will perish. What is outside it does not concern men to explore and is not within the grasp of the human mind to guess.

Which is reminiscent of Alexander Pope's couplet: 'Know then thyself, presume not God to scan; the proper study of mankind is man.' But Pliny the Elder attempts it nevertheless, in a mishmash of deism and agnosticism that echoes French Revolutionary utilitarianism in theology:

In the midst of these moves the sun, whose magnitude and power are the greatest, and who is the ruler not only of the seasons and of the lands; but even of the stars themselves and of the heaven. Taking into account all that he effects, we must believe him to be the soul, or more precisely the mind, of the whole world, the supreme ruling principle and divinity of nature. He furnishes the world with light and removes darkness, he obscures and he illumines the rest of the stars, he regulates in accord with nature's precedent the changes of the seasons and the continuous rebirth of the year, he dissipates the gloom of heaven and even calms the storm-clouds of the mind of man, he lends his light to the rest of the stars also; he is glorious and pre-eminent, all-seeing and even all-hearing[. T]his I observe that Homer the prince of literature held to be true in the case of the sun alone.

Source: Natural History (1938). First published in the year 77 CE by Pliny the Elder, translated by H. Rackham (vols. 1-5, 9), W.H.S. Jones (vols. 6-8), and D.E. Eichholz (vol. 10). via Wikisource (Retrieved January 23, 2022)

***

Hans Christian Andersen, less abstractly, married Greek, modern morality, and Victorian-era geography in his 19th century fairy tale, "The Garden of Paradise."

It was the North Wind who came in, and bringing with him a cold, piercing blast; large hailstones rattled on the floor, and snow-flakes were scattered around in all directions. He wore a bearskin dress and cloak. His sealskin cap was drawn over his ears, long icicles hung from his beard, and one hailstone after another rolled from the collar of his jacket.

BALANCING the cruelty and benevolence of the winds, and generalizing largely about the quarters of the Earth represented by the cardinal points of the compass, Andersen has the North Wind tell this account to the Wind's mother and to a prince who is visiting their cave:

|

| "Chasse aux Morses" From Le monde de la mer (1866) by Lackerbauer reproducing M Gudin & M. Biard via Wikimedia Commons |

“I come from the polar seas,” he said; “I have been on the Bear’s Island with the Russian walrus-hunters, I sat and slept at the helm of their ship, as they sailed away from North Cape. Sometimes when I woke, the storm-birds would fly about my legs. They are curious birds; they give one flap with their wings, and then on their outstretched pinions soar far away.”

“Don’t make such a long story of it,” said the mother of the Winds; “what sort of a place is Bear’s Island?”

|

| "Diana and Chase in the Arctic" by James H. Wheldon (c. 1832–1895) Painting in the Hull Maritime Museum. via Wikimedia Commons |

He delves into a walrus hunt on Bear Island:

“The harpoon was flung into the breast of the walrus, so that a smoking stream of blood spirted forth like a fountain, and besprinkled the ice. Then I thought of my own game; I began to blow, and set my own ships, the great icebergs sailing, so that they might crush the boats. Oh, how the sailors howled and cried out! but I howled louder than they. They were obliged to unload their cargo, and throw their chests and the dead walruses on the ice. Then I sprinkled snow over them, and left them in their crushed boats to drift southward, and to taste salt water. They will never return to Bear’s Island.”

(Original Danish: "Så gik det på Fangst! Harpunen blev sat i Hvalrossens Bryst, så den dampende Blodstråle stod som et Springvand over Isen. Da tænkte jeg også på mit Spil! jeg blæste op, lod mine Seilere, de klippehøie Iisfjelde, klemme Bådene inde; hui hvor man peb, og hvor man skreg, men jeg peb høiere! de døde Hval-Kroppe, Kister og Tougværk måtte de pakke ud på Isen! jeg rystede Snee-Flokkene om dem og lod dem i de indklemte Fartøier drive Syd på med Fangsten, for der at smage Saltvand. De komme aldrig meer til Beeren-Eiland!" via Wikisource.)

His mother does not approve:

“So you have done mischief,” said the mother of the Winds.

“I shall leave others to tell the good I have done,” he replied.

Source: Hans Andersen's Fairy Tales (1888). Hans Christian Andersen, translated by Mrs. H. B. Paull. London and New York: Frederick Warne and Co., pages 385–395. Via Wikisource. (Retrieved January 23, 2022)

|

| From Animals in action (1901) by Elbridge S. Brooks via Wikimedia Commons |

***

In a parallel to Pliny the Elder, Snorri Sturluson writes, in his Prose Edda, both of a deity who rules all creation, and of Earth as a separate feminine entity.

Here his picture of nature is quite 'secular,' for lack of a better word:

Another quality of the earth is, that in each year grass and flowers grow upon the earth, and in the same year all that growth falls away and withers; it is even so with beasts and birds: hair and feathers grow and fall away each year.

But in a later passage he spiritualizes the Earth:

the earth was quick, and had life with some manner of nature of its own; and they understood that she was wondrous old in years and mighty in kind: she nourished all that lived, and she took to herself all that died. Therefore they gave her a name, and traced the number of their generations from her.

Source: Translation by Arthur Gilchrist Brodeur (p. 4 and p. 5 via Internet Archive)

While parts of winter, like ice, are given inanimate roles in the Norse myths that he recounts, he does mention a cosmogony that blends fire and ice:

What was the shape of things ere the races were yet mingled , and the folk of men crew? Then said Har: Those rivers that are called Elivagar, when they were come so far from their springhead that the quick venom which flowed with them hardened, as dross that runs out of the fire, then became that ice; and when the ice stood still and ran not, then gathered over it that damp which arose from the venom and froze to rime; and the rime waxed, each (layer) over the other, all into Ginniinga-gap. Then spake Jafnhar: Ginniinga-gap which looked toward the north parts was filled with thick and heavy ice and rime, and everywhere within were fogs and gusts; but the south side of Ginniinga-gap was lightened by the the sparks and gledes that flew out of Muspellheim. [Translation by George Web Dasent, p. 5 via Internet Archive]

When he begins to set forth Odin, Loki, and the other familiar figures, summer and winter are personified, separately, as Sumarr and Vetr, in an arguably laconic paragraph (we never hear of these figures again, I think):

But the father of Winter is variously called Vindljóni or Vindsvalr; he is the son of Vásadr; and these were kinsmen grim and chilly-breasted, and Winter has their temper. [Brodeur, p. 33]

"Summer and Vetr" [Wikipedia]

***

In an old Irish poem, translated by Lady Augusta Gregory and published in 1919, "The Hag of Beare":

The stone of the kings on Feman; the chair of Ronan in Bregia; it is long since storms have wrecked them, they are old mouldering gravestones.

The wave of the great sea is speaking; the winter is striking us with it; I do not look to welcome to-day Fermuid son of Mugh.

I know what they are doing; they are rowing through the reeds of the ford of Alma; it is cold is the place where they sleep.

A hundred-year-old grandmother, the narrator deepens the metaphorical comparison of winter to human mortality. Then a tree metaphor mixes with references to Christianity in the next verses, reflecting — backhandedly, I think — the missionaries' ambivalent role in 9th century medieval Ireland.

Amen, great is the pity; every acorn has to drop. After feasting with shining candles, to be in the darkness of a prayer-house.

(The poem is also worth reading to its end for its wonderful flood-ebb metaphor.)

The Old Woman of Beara is pretty syncretic. — This page is a fair index to her traditions, with photographs of the landscapes her legend grew amongst, as well as the Wikipedia summary. —

An Irish goddess, a nun, perhaps both — in the poem that Lady Gregory translated she appears to be a sufferer of winter, but elsewhere she appears to be the bearer of winter.

***

Sources:

"The Hag of Beare." translated by Lady Augusta Persse Gregory (1852-1932) in The Kiltartan Poetry Book. New York: G. Putnam's Sons, 1919. pp. 68-71. (via A Celebration of Women Writers, University of Pennsylvania)

"The Hag of Beara" [Wikipedia]

No comments:

Post a Comment